Afton Wolfe on "Ophiuchus": Astronomy, Vulnerability, and the Sacred Calling of Art

Singer-songwriter Afton Wolfe discusses his album “Ophiuchus,” named after the 13th zodiac constellation. He explores themes of astronomy versus astrology, the balance between high concepts and intimate moments, vulnerability in songwriting, and navigating the attention economy as an artist. Wolfe also shares the deeply personal story behind “Crooked Roads,” written the night before his wife’s brain surgery, and reflects on the collaborative process with illustrator Cora Lee.

Transcript

(Lightly edited for clarity)

The Forgotten Constellation

Cris Cohen: How do you pronounce the name of the album?

Afton Wolfe: Ophiuchus, I think. That’s one that a lot of people haven’t heard of, that particular sign within the Zodiac. I’ve studied astronomy, esoteric practices, occultism, magic, things like that. The concept came from realizing that the sun was actually in that constellation when I was born. I started looking at the history of the horoscope and the Zodiac and realized that those dates were set two thousand years ago and nobody’s really questioned it since then.

Some people do. They call themselves sidereal astrologers. But for the most part, what’s in The New York Times and fortune cookies is based on antiquated astronomy. The stars are moving, right? Polaris was named because it lined up with the North Pole, but if you use it as a guiding light now, you’re going to be going in a little circle on the side of the Earth, because Vega is actually closer to the North Pole.

On top of the fact that I’ve been lied to my entire life about being a Sagittarius, I like the idea of combining materialism and esoteric mysticism. I think that so many people choose one or the other when the answer is both.

As Above, So Below

Cris Cohen: The album has this very high concept about the zodiac and the movement of the sun, but when you drill down to each song and lyric, it’s very much focused on the little moments in front of us. How often are those two elements in sync versus bumping up against each other as warring factions?

Afton Wolfe: Those are two things that have been talked about for thousands of years in different ways. It’s not something I necessarily deliberately did. Aleister Crowley used to say “as above, so below.” The big, high-concept stuff and the little, granular, detail stuff definitely coincide and harmonize, just like when you look at a flower and it has the same pattern as a galaxy.

But at the same time, there’s the concept of yin and yang. There’s always conflict between conceptual stuff and practical things. That’s what moves us along, that balance that is never completely in balance because then it’d be static. But it always kind of on the aggregate exists.

Cris Cohen: What amazes me is that you were able to craft songs to go along with each stage and even rolled them out to the general public in sync with their corresponding Zodiac dates. How do you cram the muse into a plan?

Afton Wolfe: A lot of this was conceptual and I just kind of let it go. Some of these songs are relatively old, some are very recent discoveries. I try to frame songwriting as discovery. I don’t like to think that I made it or crafted it. I find it. Maybe if I do anything after that, it’s like arranging flowers in a bouquet or shaping gold into jewelry. But the gold itself is something I find.

I tried my best to think about whether each song goes with its astrological sign traditionally. But with all astrological signs, we’ve associated them with vague characteristics that if you’re told over and over you have the traits of a Virgo, then you start to become that. Social factors are certainly more influential on most people’s lives than celestial ones.

The Meaning We Create

Afton Wolfe: If there’s anything I’m always trying to do cerebrally or academically, it’s to express that existential philosophy, that we are the ones that decide what is important. One of my favorite examples is the Olympics. When you watch late-night coverage and see the Polish indoor volleyball team that’s going to finish dead last, you realize there’s a group of people in Warsaw to whom indoor volleyball is the most important thing in their lives. They’re not going to be successful at it on a grand scale, but for four years they dedicate themselves to this.

I see it hungover at eight in the morning on a Sunday and think these guys are clowns. But they would probably look at the fact that I’m spending all of my time, energy, and thought trying to come up with conceptual, artistic ways to share my music and think, “It’s just music, man.” Whereas I’m like, “It’s just indoor volleyball, guys.”

We put the meanings on these zodiac signs, on religion, politics, money. To me, it’s music. That connection is what I find important. I think it’s something that connects me to lives and spirits and realities way outside of my own fifty to a hundred years on this planet. I think it’s something that’s been going through me forever.

Leaning In: Vulnerability and Connection

Cris Cohen: A lot of these songs have a very intimate feel. With “Rules of War,” you’re kind of leaning in vocally. How did you get comfortable with that? There’s a vulnerability that comes with it.

Afton Wolfe: I take that as a compliment because to me that is where I am able to open up and receive connection as well as give it out, by making myself vulnerable. My last few releases were of other people’s songs. The last multi-song thing I did was all of my father-in-law’s songs.

One of the reasons I wanted to make this a full-length album with many different kinds of songs is because I wanted it to represent what I aspire to in music: personal, vulnerable connection to people that are willing to send it back to me. I want to be open to it.

It’s a very personal album. All the songs I either wrote or co-wrote. I talk about things that are very important to me, things I’ve been meditating on for years… forgiveness, war, philosophy, ontology, mythology. I don’t know who else they’re important to, but I tried my best to bring in as many different influences because that is something that’s important to me.

I’ve got four different drummers on this record, five different keyboard players. Only one bass player… Daniel Seymour is my guy forever. I wanted each song to have its own personality and to reflect something I feel is very important and care about a lot.

Cris Cohen: Is that vulnerability difficult to recreate in a live setting where there are people drinking and all that?

Afton Wolfe: It’s the opposite. I honestly feel more vulnerable the less the crowd is listening. When the audience is really paying attention and locked into me, I feel like we’re together. We’re both vulnerable, but we’ve got each other.

When I’m playing to a bunch of people that aren’t necessarily interested or trying to have a conversation, I feel more vulnerable. But that kind of fuels me. I don’t get louder. I get quieter and more within myself. Strangely, when I get quieter, people tend to quiet down too and start connecting and paying attention.

When I was younger, I was a lot more ego. I’m still plenty of ego now, but I see it. I see where it is most of the time and I can set it aside. Whereas when I was younger, I was utterly convinced that I was the smartest person on earth, like many young people are, then demonstrably proven wrong.

Writing Through Crisis: “Crooked Roads”

Cris Cohen: Songs like “Crooked Roads” allude to the medical trials and tribulations your wife has undergone. Is that a song you wanted to write or had to write?

Afton Wolfe: It was unavoidable. Had things turned out differently, it wouldn’t have made the album. I finished that song the night before she went into surgery, December 5th. I had it kind of written, but that melody and a few phrases — the very first phrase “on the life of what you expected” and the very last phrase — just wouldn’t get out of my mind.

While we were going through all that anxiety, it was whatever I could put my mind on to keep moving forward and stay away from fear and casting bad magic and negative energy into the world. I tried to put in positive energy and gratitude. Hopefully you receive that, and we did.

The night before, I was sitting at the piano and those lines came to me: “We’re going to make it through the 6th of December, till then all power and guidance and wisdom to Dr. Sarah Bick,” who was her neurosurgeon. I think I found that and was able to reinforce her doctor’s utmost confidence, wisdom, power, and competence, along with my wife’s unbelievable courage and strength and steadiness throughout that entire process.

It also happened to rhyme with the line before it: “It’s the best life that I can remember,” because I don’t know if it’s the best life I’ve ever had. That made sense and rhymed with December.

Cris Cohen: How do you shift from the therapy of getting it out of your system to being the editor asking, “Is this a good song?”

Afton Wolfe: That’s a great question. I try not to put too much value judgments on songs because different people have different values. If everybody liked it, it wouldn’t be art, it’d be dopamine.

I know that, for me, a good song is one that’s sincere. I cry still every time I play that song. It brings me back to those times. To me, that’s what makes it a good song. I mean it.

When I play it, I am back in that period of time. Not even necessarily that period, but two weeks later when everything had unwound and she was fine. When we walked into the hospital room right after her surgery and she was cracking jokes. That’s the time it puts me in. That gratitude and relief. God, we made it.

The Power of Silence and Space

Cris Cohen: In “Rules of War,” there are points when it just stops and you get absolute silence for a second. It’s quite dramatic, but I would think a younger songwriter wouldn’t have the knowledge or courage to do that.

Afton Wolfe: Maybe I’m fortunate, but to me, the dynamic, the rest, the push and pull… that’s what moves me when I’m really feeling the song intensely. That song was written so fast, it was crazy.

I had a songwriting appointment in Nashville. I rarely get anything done during those things, but I use them as a pretext to hang out with cool people. I hate putting pressure on finishing the song. I just bought an Omnicord, a 1984 Suzuki Omnicord. It’s not a toy. It’s a wonderful instrument, an ‘80s spacey synthesizer harp combination.

I brought it over to Judy Blank’s house. She’s got this slacker space pop kind of thing that I absolutely love. Talk about a brilliant craftsperson of songs. She pulled it out and started messing around with it. My intention was to write a song about alien pancakes. I’d just read this story about an old farmer in the ‘60s in Wisconsin that got visited by extraterrestrials and they gave him pancakes and left.

But she turned the synth beat to tango and started playing. The entire chord progression worked out in 45 minutes. We don’t have any words. It was definitely not a song about alien pancakes.

I opened up my notebook and it only had one little scribble in there, a concept I’d been thinking about. The meter and the idea and all of it just worked perfectly. The whole song was 95 percent the shape it is now in like two hours. One of those unavoidable things. Somebody was going to find it. Thank goodness it was me and Judy.

Less Is More: “Rushing Back”

Cris Cohen: Another example of experienced songwriting is “Rushing Back”. There aren’t many words in it, but it says a lot.

Afton Wolfe: I really appreciate that you picked up on that. I personally think that’s one of my favorite songs on there. That one sentence says a lot. I had someone very close to me that I lost. That’s an older song, probably twenty years old. I wrote it in a van with an old band on my way to Nashville for the very first time, still living back in Mississippi.

I was just depressed. I had been writing down all these details, clever stories, descriptive terms. Maybe one day I’ll write a short story or novella about this person’s life. But the overwhelming thing was that I couldn’t stop the memories. There was nothing else that I really needed to say. That was how I was feeling. Every little thing was rushing back.

Of course, you have to have brilliant musicians like Seth Fox, Dan Seymour, and Zach Douglas playing all those wonderful notes to keep it from being boring.

Cris Cohen: A younger songwriter would have tried to cram in as many words as possible.

Afton Wolfe: I was a younger songwriter and did that. This was the result of letting go and saying, “No, this is what the song says. All this other stuff might be another song, another flower, another piece of gold, another piece of jewelry. But this song says this. It says every little thing comes rushing back.”

If you want to call it maturity, I certainly will cop to that. There’s more salt in the beard every day. But it’s also realizing that it’s not my ego that’s making these songs, it’s discovering them. Just like the Buddhist philosophers say, you’ve never seen a picture of an ugly wave. You’ve never seen a misshapen cloud. That’s what a song is. When you put a song in a box, you can’t put a wave in a box. You can’t put a cloud in a box.

Attention and the Nature of Light

Cris Cohen: In your essay accompanying the album, you discuss the weaponization of attention and how it’s a struggle for art to exist in this current world.

Afton Wolfe: The spreadsheets seem to go up as human attention span goes down. They’re inversely related. I think it’s one of the most important discoveries of humanity and we don’t talk about it enough: attention changes the nature of light.

I studied physics in college. I got a minor in it because the math got too hard, but the concepts were fascinating. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle: if you are measuring light as if it is a wave, it will act like a wave. If you are measuring light as if it is a particle, it will act like a particle. So the observer changes the nature of light.

That’s why the Buddhists and the Hindus and ancient societies, even early Christians, Judaism, Islam… there’s so much emphasis on prayer, meditation, silent reflection. That is the exercise of your attention. It’s really hard. We’ve convinced ourselves that it’s laziness to do that, that to be quiet and still is counterproductive when it’s not.

One of the main reasons we’re having the amount of problems we are in society is because people think they have to be focused on something in the material world constantly instead of quiet reflection. It’s not a religious thing, but it’s something that humans have understood on a core level for a long time. We’ve forgotten very recently en masse.

Cris Cohen: How does the artist move forward in this world?

Afton Wolfe: It’s difficult. I do it by having something else provide me with an income. I can’t be an artist alone. I have to work and make money so I can afford to make my art because the art is not profitable. It doesn’t show up on the bottom of the spreadsheet. The supply-demand curve is not in the artist’s favor.

I think meditation and constantly questioning why you’re doing it and understanding why you’re doing it… making sure you’re not doing it for recognition, admiration, wealth. To me, it is either a mental disorder or an ancient sacred calling. Probably both, but they both deserve respect.

If I’m not hurting anybody, then my mental disorder is benign. But I do believe it’s an ancient and sacred thing that needs to happen. We can listen to beautiful recordings of the past, that’s why the supply-demand curve doesn’t work in our favor. Every billion songs that come out every week are economically competing with the Beatles and Led Zeppelin and Bach.

But we’re compelled to find what’s next. I think our species depends on it, depends on artists finding what’s next and showing us what’s important. I want to be a part of that. I’m compelled to. If I had a choice about this, this would be a dumb choice. I’m going to work a full-time job so I can work another full-time job that doesn’t pay me because it satisfies my soul or solves my mental disorder, whatever the case may be.

Collaboration with Cora Lee

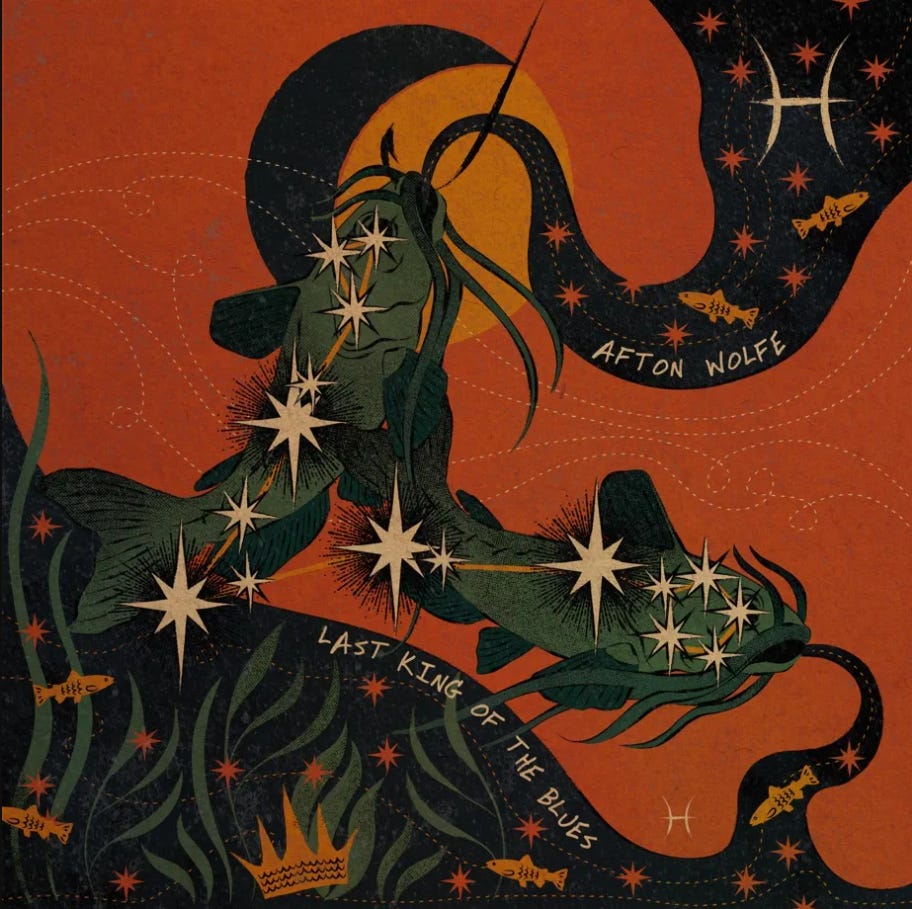

Afton Wolfe: One of the things that has really tied this project together and made it even more important has been the art of Cora Lee. She’s made illustrations for each one of these songs. Her magnificent art has been a brush of wind on a dying fire so many times over the last year. She’s inspired me, collaborated with me.

If you pre-order the album, you’re going to get a booklet of the lyrics and her illustrations. I just got them in today. They are beautiful. She’s made sacrifices to get these out. I’ve made that poor woman work harder than she ever thought when I brought this idea to her over a year ago.

The illustrations are fantastically beautiful. She’s included so much symbolism and thoughtful care.

Cris Cohen: Did you give her any direction or did she listen to early demos?

Afton Wolfe: She listened to the songs. This plan got into place before most of the album was even tracked. I started releasing songs before it was finished recording. She’s been doing these illustrations as I get the song done and give it to her.

I didn’t really give her many suggestions. Most of the illustrations she sent to me, I was like, “Perfect. Amazing.” We had some discussion about the typeface and font. I wanted there to be some through line, and we finally landed on my handwriting for each one of them. I made a font out of my handwriting. That’s worked perfectly with the vintage style and personal detail and care she’s put into it.

Really the only other thing is that Pisces was “Last King of the Blues,” so I asked her nicely if they could be catfish. She was agreeable to that idea.

She’s a brilliant artist. On top of that, she’s actually also probably my favorite songwriter, in the top three or four of my favorite songwriters in this town. I admire her and everything she puts out artistically. It’s just stunning.

Afton Wolfe website: https://aftonwolfe.com/

Bands To Fans

I help professional musicians build a better connection with their fans by developing custom social media content that delves into the stories behind their songs, albums, performances, creative process, etc. Visit my website to learn more.