From the archives, an interview I did with Andy Summers of The Police back in 1999. We discussed:

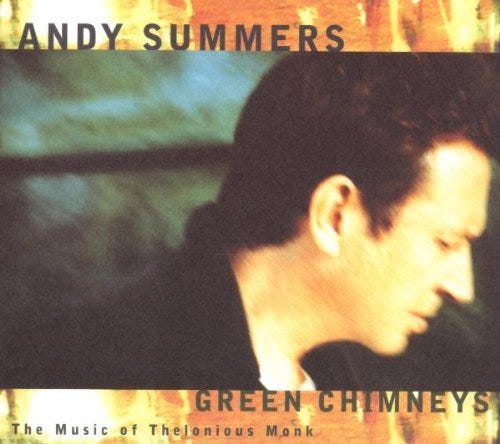

His solo album "Green Chimneys: The Music of Thelonious Monk"

Playing songs on the guitar that were created for the piano

Internalizing the Thelonious Monk repertoire

Why he mixed the album twice

Getting Sting to sing on “Round Midnight”

Jazz guitar versus rock guitar

Andy Summers website: https://andysummers.com/

(This transcript has been slightly edited for clarity. Images from artist website.)

Green Chimneys

Cris Cohen: Regarding your album “Green Chimneys: The Music of Thelonious Monk,” what are the challenges in playing pieces on the guitar that were created for the piano?

Andy Summers: Well, that's a good question. I guess the challenge is to make it sound authentic on the guitar, which specifically for me involved things like changing keys, which of course some people think is sacrilegious. I think that is a little purist.

For example, a piece like “Round Midnight” was composed in the key of E flat minor, which is difficult on the... not difficult, but it doesn't give you a lot on the guitar in terms of the guitar voices. If you move it up one fret or half a step, you get into E minor, which is, of course, basically the key the guitar is in. And you’ve got a lot of open strings, a lot of very interesting dissonances and open voicings that you wouldn't get in E flat minor. So it starts to really sound like a guitar piece then. It can sound a lot more beautiful, actually. There's a lot of stuff you can do, which is not available in E flat minor.

In fact, this is a slightly weird one. On “Round Midnight” what I did was to play it as if the guitar was in the position of the open E minor, but in fact I de-tuned the whole guitar a half step. So in fact, it's authentically in E flat minor but made available on the guitar with the open string. I don't know if you can follow that.

Cris Cohen: Yeah. It's almost like you're tricking yourself.

Andy Summers: I wanted it to have the dissonant voicings available to me, but that meant to achieve that, I played it as if in E minor, but in fact with the guitar tuned down. Things like that. I would change keys slightly, find ways to play the heads, or the actual compositions, with open strings, slides, slurs, harmonics, hammers… to make it sound distinctive. Rather than just playing everything fretted and just like I'm just playing the tune without really thinking about it in terms of the guitar itself. So, I was pretty specific about that.

Cris Cohen: Just in switching from the main instrument, from a piano to a guitar, you are obviously putting your own spin on everything. Were there any people who were nervous about the idea of just even doing that, of taking away the piano as the backbone?

Andy Summers: To me, the first consideration is, "Right. Okay. There's no piano on the track." It seemed the most obvious move to me because it's my record, Andy Summers. It's like, "Okay. I'm not putting any piano on this record because what's the point?" There's organ on it, but it moves away. It's distinct enough and un-Monk-like enough that it was okay as a texture. But I mean, why would you want to use piano on a Thelonious Monk record unless you were just another pianist doing Monk?

For me, I wanted to make it very fresh and have the Monk sound, as far as I could achieve it, in a way that it hadn't been heard before.

But I mean, all these things were in my head. I was thinking about them. For instance, I tried to do a left-handed piano on “Bemsha Swing” with the dobro, because it's got more like a piano sound. And try and think about Monk's passable, off-the-wall approaches to playing solos on some of the solo aspects.

To a degree, you're self-conscious about it. I'm thinking about Monk. I've got in my head (that) I want to be respectful and pay homage. But at the same time, you want to have your own voice in there. So, it's a lot of things.

And some of it is just playing it and thinking back and wondering if you've got it or not. And maybe not listening to it for a while and then come back, listen to what you did, and seeing if it sounds authentic. Doing a record like this is a real challenge in a way. And in some ways harder than just doing your own stuff. Because a lot of people have done Monk. And you're trying to present it differently and have it come off as, not just a failed attempt, but to have spirit. It's easier and more difficult, both at the same time.

Internalizing the Monk Repertoire

Cris Cohen: And it sounds like with this, more than traditional albums, a lot of planning had to go into it before you even began the recording process, mapping things out?

Andy Summers: Well, there's a lot of preparation in terms of internalizing the Monk music, or the Monk repertoire. There were certain things I did. You can prepare, but of course, you're playing jazz, so I think it's more like internal preparation. And then you've got to try and be spontaneous. But hopefully out of all that internal preparation, the right thing is going to emerge.

On that, I stopped listening to anything else for a couple of months before I made this record. I only listened to Monk. I stopped listening to any other kind of music. I had also gone through the whole repertoire, which was about 90 pieces, and sorted them into categories, decided which ones had been played too much, listened to some undiscovered gems I could bring out, played most of them on the guitar. I worked right the way through it, so I was pretty much into it. By the time it got around to recording, I was very familiar with it and I'd saturated with it. I felt that I could be in the right place to play it.

Cris Cohen: Was it then difficult getting out of that mindset once you had finished the project?

Andy Summers: No, it was fine. I'm not totally out of it really, because I'm out now playing it. It's all I'm playing because the record's out. So to back up the whole event, I play my own older material as well, but I'm currently playing a lot of the pieces off the album.

It took me a while to put this whole record together. It was a rigorous mental discipline, where I just stayed with the program. And in some ways, at the end of all that, once the record was done, it was nice to let go of it a bit and return to some of the earlier stuff I was playing. And it all seemed very easy after that.

Sound Quality

Cris Cohen: Now, one of the first things you notice when comparing Monk's recordings to yours is the difference in the quality of sound, quite obviously because you had much different recording materials available to you than he did. Was there ever any concern about making the songs too clean or too crisp?

Andy Summers: Well, it's a good thought. Yeah, I understood what you were saying, but I guess the way I almost visualized it was that everything's just going to sound much clearer and fresh because of what we can bring to recordings now, the actual recording quality. No, I saw that as a plus actually.

Cris Cohen: So it's like when you pick up an older vinyl album and you think, "If only he had the kind of recording equipment I have access to, how much better we could have heard him."

Andy Summers: And also, personally, I like recordings to be… I mean, this is always just something I have to go through with every engineer. Because engineers will tend to separate everything out and make them very clean, because that's what they do. And I always try and keep things a little rough, a little murky sounding, punchier. I don't like things to be too audiophile, as it were, because I think it tends to take away from the richness of the music sometimes.

It's a hard thing to talk about it, because that's when you're in the mixing mode. In fact, I mixed this record twice. First time, we were pretty exhausted. It was just before Christmas. We both went off for a couple of weeks. I came back and I knew that (the mixes) could be better.

I think we both returned and felt at the same place. We virtually remixed the whole album, because it was like we had a better take on it. We were fresher and the second time we got it right, I think. It definitely came out a lot stronger.

Cris Cohen: And then not only with this album, but with your other work, has that been a struggle trying to maintain the warmth to the sound in and amongst all this technology and advancements?

Andy Summers: Yeah. It's always something that I have to deal with, telling them, "Not too clean. No, it's too clean. It's too much reverb. Everything sounds too separated. Make it sound more like a band."

That's always a personal aesthetic. And we’ve got all of this digital technology. I have to always fight to keep it more analog sounding. But I work with a brilliant engineer who is very hip to all that stuff. And it was interesting doing this one, because it was the first time I ever recorded straight to disc, with the new system, the RADAR system. But it sounds fantastic. And it's so easy to use now. It gives you so much creative edge as you're going along.

Cris Cohen: So it'll probably be the method you use to record in the future?

Andy Summers: Oh, I think so. Yeah. It's so fast. Waiting for tape spool to wind back now is like, "Oh my God. I can't be bothered." With the RADAR system, you just press the button and you're straight back to where you were. It's a real time saver.

But it sounds great too.

Sting

Cris Cohen: Now earlier you brought up the tune “Round Midnight.” Why did you have Sting do the vocals on that track?

Andy Summers: There's the obvious reason that everyone likes to see him and I connected on something. But also, he does sing this with that husky, non-vibrato quality he's got that I thought was perfect for this. So it's just a nice thing that everybody would like. But the truth is, he can sing this stuff really well. So, it wasn't difficult to put together.

I called and asked if he was interested in doing it. He was very responsive. It was on me then to construct the backing track that he could put the vocal on. I did (that) and then flew to Italy, where he was living, to get him on it. It was a good experience.

Jazz vs Rock

Cris Cohen: Oh, very cool. And just a few weeks ago I interviewed Bill Evans, who…

Andy Summers: Oh, Bill Evans the saxophone player? Great guy.

Cris Cohen: I asked him about you. He said that you are a musician with vision, that you look at your study of the guitar as a lifelong learning process. Now the question I have is: How does learning via jazz differ from learning via rock?

Andy Summers: How does it differ? Boy, how do you answer that question?

Well, I mean, you're specifically learning different things. You're learning a different rhythmic feel. The feel of a jazz solo is very different than a rock solo. Let's see how much of this I can articulate. When you play rock solos, the music is much more strict. You play in eighth notes that are much stricter and on the beat than in jazz.

Jazz is a lot sexier. The accents come in different places. It's a very different feel. But it's the emphasis of the accents. Rock, compared to jazz improvisation -- and this is a real generalization -- it's a lot stiffer. Jazz is much looser and sexier. But in musical terms, it's the placement of the accents.

I mean, these are generalizations, but that's what you would be working on. And you would take a long time to really get the feel of where a solo goes. But then it's much, much deeper than that even, because you're talking about a major area here. How do you construct a great solo? Because in jazz it should be an unfolding, it should be a narrative. It should be an unfolding of a series of ideas that goes on a little journey. Rock can be like that, but less so in rock. But in a jazz solo, you would tend to build it and you build on the ideas that went before. You play in motifs, play inside and outside of the harmony. It's very rich and deep. It's life. Rock solos tend to be in the middle of a song where someone's singing and…

Cris Cohen: Yeah, and more abrasive.

Andy Summers: Oh yeah. And obviously much more abrasive. It's a whole different feel. But if you're going to play good jazz on a guitar, then you've got to really study harmony in depth. It's a lifetime study. You never finish. You master it, but you never master it, really. You never get all of it, no matter how many years you put in.

Rock is obviously a lot simpler harmonically. You don't need quite the depth of harmony. Though personally, I think the more you know, the more you bring to any field, and then you shape it.

Certainly, in The Police, I was just very loaded with jazz and classical studies, but I was playing rock. But I was able to open up the rock parameters by bringing these other elements in. It just made it interesting for people. Not esoteric. Because the main thing is the rhythm… the drums were still there playing in a rock style. And I was able to float all these different things in and out that weren't in the normal, conventional rock style at the time.

I think jazz -- I hate to make these comparisons because they're sort of odious -- I think it's the deepest study. It is more difficult to play it really well at the right depth or the right level. You've got to put in a great deal of time. It's a deep, intellectual, lifetime study.

The problem with rock, for me, is that I get bored with it. I get bored with the rhythms, particularly. The drumming gets boring for me because it's not loose enough. I find it very wooden and stiff compared to jazz.

Cris Cohen: Jazz has a more organic feel.

Andy Summers: Yeah, much more organic. It's looser. It’s much more with the body. I find it a lot sexier. Rock is very stiff to me.

Improvisation

Cris Cohen: Last fall, I interviewed Billy Cobham and he described his playing in jazz and drumming as: He always thinks of it as he's writing a letter to someone. And so that seems to be what you were talking about.

Andy Summers: It is. It's a narrative, if it comes from the right place. I go out now and I usually play with the trio. I stand there for a couple of hours on the stage and I play these beautiful tunes, and then I improvise.

Basically, improvisation is on-the-spot composition. But playing jazz like that and trying to play deep, it's a real mirror of where you are at the time. What's in your head, your physicality, the room, how you feel about your life… it really mirrors all these things. And that's what I love about it. There's a truth to it. That when you really just stand there and you're just trying to play naked in the space, then it's like you're really attaching to sort of a life process.

It's some hard stuff to talk about. It sounds mystical, which is what it is in a way. Words cannot describe it. Except when it's happening, at the right level, you connect to something. I don’t want to get a bit religious, but it is sort of talking to a higher power or something. You do get connected in a way that is deep and hard to talk about, but is very satisfying. Like when you connect with a score. It doesn't happen every time. But in the really great moments, when it's happening like that, it's a wonderful thing.

Cris Cohen: And also I think for the listener too, especially at a live performance.

Andy Summers: Yeah. People know. I think particularly the audiences in this country, which are very musical, people connect with it. They know when you're there. It's wonderful.

His Distinctive Guitar Sound

Cris Cohen: Another thing that Bill Evans said -- and which a lot of people have said -- is that you have one of the most distinctive guitar sounds in music. Is this ever a burden? Do you ever find yourself unconsciously…

Andy Summers: That's a good question. Yeah. And probably a lot of people mean The Police by that. Well, it's very nice, but you don't even want to get stuck with that, really. You want to be able to keep moving on as much as you can. But I don't know. I think you just go on and you keep doing what you're doing. You can reshape it. But I think it can be a burden if people mean, "Well, why don't you just play just like you did in The Police?" Well, that was a long time ago now. I did that. I've gone to somewhere else with it, which I think for me right now is a lot more interesting. But I hope that, whatever it is, it's your own touch and it comes out anyway. I mean, I think I've still got that.

Bands To Fans: We help musicians tell their stories via social media, websites, etc.