Emily Saliers of the Indigo Girls | Interview

Cris Cohen interviews Emily Saliers of the Indigo Girls (this interview was done in August of 2018). They discuss:

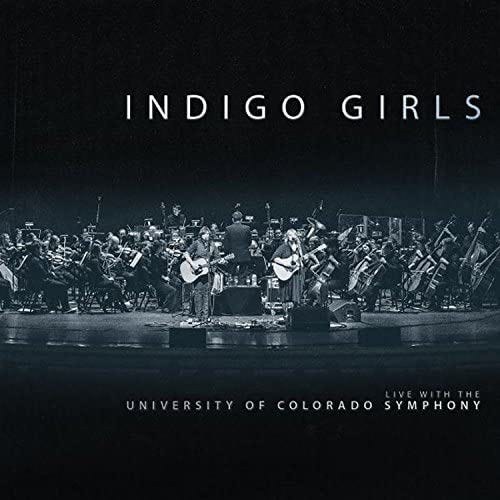

Their new live album, which they recorded with the University of Colorado Symphony Orchestra

How putting this show together has influenced her songwriting going forward

How alternative guitar tunings have led to the creation of some her most well-known songs

And more

Performing With An Orchestra

Cris Cohen: What was the most challenging part of performing with an orchestra?

Emily Saliers: It was more challenging at the beginning of our journey of playing with orchestras -- so, it got better over time -- but for me, it was... Amy and I are used to playing our songs pretty much in metric time. Or at least pretty steady, in terms of tempo.

When we got with orchestras, sometimes there was a latency of sound from either the percussion or the timpani at the back of the hall where the orchestra was. There would be that slight delay. And so, it was a bit disorienting to have to try to play through the songs, and keep some center of time.

Sound latency was, for me at first, a very, very challenging part of it. And then, as we got more experienced -- I don't know if I can speak for Amy, if that was the most difficult thing for her -- but for me, the more we did it, the more I relaxed with that. You sort of fall into this middle place when you've got the amorphous orchestra. And then you've got me and Amy strumming away.

Cris Cohen: It kind of reminds me of reading about singers who have sung the National Anthem at stadiums. They talk about the challenge of, there's a delay, and the sound reverberates and comes back at you off of that. It's like you're part of it, but you're kind of screening it out at the same time.

Emily Saliers: Yeah. For me for a while, it took a lot of focus to just perform the songs. It made me kind of tense, to make sure I was in time with the orchestra. But also, the conductors are very, very good. Because they have to do pop shows like this, most of them are pretty good at reigning in the tempo and keeping it together.

And then, I just simply got used to the slight fluctuations that were challenging for me at the beginning. So now I can really just play the songs without thinking. Early on it was a lot of thinking, a lot of inner tension. And now it's much more free and a totally awesome experience to hear all that music behind our songs.

Working With Great Arrangers

Cris Cohen: Amy said in an interview, "We didn't want to just slap some classical music on an Indigo Girls track and call it a day." So, what did you guys do to ensure that did not happen?

Emily Saliers: Well, we picked really, really good arrangers, musicians. I first worked with Steven Barbara on my songs. And then Amy picked Sean O'Loughlin. And now all our songs are done by Sean. And Sean is just... his ideas are creative, interesting. He knows and likes our music, so he has a sense of how he can bring it to life, because he's already familiar with some of it.

The other thing is, Amy and I have conversations with Sean as he's arranging the music. Say for instance, if Sean did a first pass through of an arrangement, sent it to Amy, a little mockup on MP3. She listened to it and she's like, "Well, this section could be a little more," I don't know if she'd use a word like “bigger.” Or "This section could be a little bit more tense."

Then Sean would know what she's talking about and go back to the drawing board and tweak the sections. So, in that sense, it was collaborative. It totally avoided just slapping music on top of our songs, being part of the process. But the most important thing is to pick the person who can really, truly orchestrate your songs in a creative way. Sean hit the jackpot for us.

Cris Cohen: Yeah. That is kind of a fascinating challenge. Because I'm assuming that the two of you have been playing together for so long you have quite the shorthand when it comes to discussing ideas, or expressing how things could be different. But then when you're suddenly working with someone arranging an orchestra, they may not have the same vocabulary. Do you have a background in symphony arranging, so that you can throw out those terminologies? Or how did you meet in the middle?

Emily Saliers: Middle ground, Amy and I have enough... We sang in the chorus in school. I grew up around sacred music and orchestral music. My parents went to go see the symphony a lot. I think for me, and for Amy certainly, we could say things like, "What if the cellos were thicker here?" Or "Maybe some bottom end." Or I would say, "Well on the record we did this arrangement, sort of like Peter Greenway. A little bit left of center and a little bit tense," and things like that.

Sean, he's got a broad sense of what people are telling him and how to translate it. So, we really didn't have any problems. We never came back after a conversation and said, "No, that's not it at all." Amy went two or three times around with him on an arrangement, maybe for one or two songs. But, for me, by the time we had a conversation the second time around, he nailed it.

Cris Cohen: Then when he's sending you these MP3s of his initial arrangements, is it layered on with pre-recorded tracks that you guys did? Or is it just the symphony instrumental?

Emily Saliers: It's just all electronic. So, in that sense, it truly is a mockup. It's not anywhere close to the bigness, grandness, and beauty when you hear the real instruments. So, the melody of... say it's “Galileo” he's arranging. All the parts of the arrangement, you can hear them, but they're played through a synthesizer or whatever, through fake strings, digital strings. Then he's clunking out the melody on a fake keyboard or something. So, you hear, "Ding, ding, ding..." It's very, very mechanical.

But that's the way you get a sense of how it all works together. Sean is so talented. Just to back up a second. Talking about interpretation of what Amy and I are trying to discuss with what we have in mind for an arrangement. The truth is, he brings so much of himself to these arrangements.

At first it was kind of challenging to get used to hearing that melody plunked out on that fake keyboard and to hear the strings be synthetic. But it's enough of a mockup to tell what the arrangement is. And then when you get to hear it live, it is like being blown away.

So, there's a little bit of trust... Well, there's a lot of trust in the arranger. And there's communication between us and him. Then there's listening to the mockup. Then you just somehow know it's right. Then you get to hear it and it's amazing.

I think orchestras get very bored doing pop concerts, where they have a lot of whole notes and things are very simple. (Like) when Amy talks about slapping classical music on pop songs or rock songs. His arrangements are interesting enough that the word is the players actually enjoy playing them. The response to the arrangements has been really, really good.

Cris Cohen: Wow. That is an interesting compliment, that it complements the music, but also, it's enough of a challenge for them, that they stay engaged with it all.

Emily Saliers: Yeah. The conductor will stop and say, "Look at measure 62," or whatever. Then he or she is pinpointing problems where it's challenging for the orchestra. So, there's enough of a challenge. They're not just reading simple eighth notes and whole notes and bored to tears with it. They're engaged and need to work on certain spots that are trickier than others.

It's very gratifying for us to hear that the players in the symphony are enjoying the arrangements. That's important to us.

Cris Cohen: And speaking of the symphony, why specifically did you guys choose the University of Colorado Symphony Orchestra for this?

Emily Saliers: Because we had done a show with them previously. Maestro Gary Lewis was an excellent conductor. We work with a lot of conductors who are certainly memorable in the whole process. They're a younger symphony, so a lot of grad students. There may have even been a couple of college students in there. They had an energy, being very present in the music.

I think sometimes an orchestra position can become a job. I can see how that would be, but it's not that way for the players in this orchestra. So, it was a tremendous amount of vibrant energy that Amy and I both hooked into.

From an economical point of view, we couldn't work with a major city symphony. The union fees are prohibitive for this particular project. So, we were just really fortunate that the orchestra that we wanted to make a record with was the one that worked out best for all the logistical and economic reasons. They're just a wonderful orchestra and conductor. We all got along really well. Unfortunately, I had strep throat during a performance, but it worked out.

Cris Cohen: During the recording?

Emily Saliers: Yeah. I was just doing my antibiotics. It was a lot of letting go. “This is going to be what it's going to be. It's going to be okay.” And in the end, it was fine, from my end of things.

Cris Cohen: Yeah. Your voice still soars in many points. There certainly isn't any indication that you were struggling through anything.

Emily Saliers: Yeah. That was one of the things. I've done this long enough that when Amy or I sometimes get sick, or have challenges with our voice, after doing this for 35 years, I've reached a point where I'm able to not get despondent about any kind of thing that's going on, but simply be in the moment of the music, and perform to the very best of my ability. Amy and I always give every bit of our heart and soul into our performances. Especially this one, because it was so important to us.

Cris Cohen: I've heard from other musicians ... Lord knows, if you perform enough shows, eventually you are going to perform sick. I've heard from a lot of musicians, it's like, once you get in the midst of the show, sometimes what's bothering you just really kind of fades temporarily. Not like you're magically well, but it really kind of slips to the back of your existence, so to speak. Did that happen here?

Emily Saliers: I would say that, yeah. It was like losing ... for me, it wasn't like losing my voice. Which, we wouldn't have been able to ... We know at what point we are unable to perform in a way that's going to be satisfying to us or to the audience. You know?

Cris Cohen: Yeah.

Emily Saliers: There have been shows in the past, not symphony shows certainly, but other shows where we had to limp through a little bit. Typically, the one who is ailing a bit and the other one is not sick at all, we sort of hold each other up through the shows.

But in this instance, it wasn't like I couldn't get notes out of my vocal cords, or anything like that. There was plenty enough voice to do what we had to do. For me, it was unfortunate that I had to have this during that time. As I say, I don't even know if I should be talking about this. I don't want anybody listening for it, the truth is. But these are the things that you can weather.

Especially as we get older, and we've done this, as I say, for 35 years. Our vocal cords need really special TLC. Lots of water, lots of rest, vocal warmups, exercises, fewer shows in a row. All those things. But now Amy and I pay very, very close attention to that.

It's like older athletes do what they can to keep their bodies so fine-tuned and working. It's like that with the voice.

Cris Cohen: Yeah, that makes complete sense. It also leads to another question I had. Most of the time you're a duo. Then you're going from being a duo to being a total of 66 musicians playing at once. How did you ensure that the vocals were not overwhelmed in that scenario? Did you have to adjust how you sang?

Emily Saliers: No. We have a front of house sound engineer who's been with us for years and years. He knows our voices intricately. He's very, very good at sound. Of course, we had all the mics set up recording it. He's done many, many, many shows with us, so he knows how to balance things.

Then there was the recorded sound. Trina Shoemaker mixed the record, and we've worked with her before. She's an incredible engineer. I can't even describe to you how many hours she's put in and how hard she worked.

There are things that you obviously have to tweak, bring to life. Sometimes you need a certain compression to bring things out. She was just masterful, altogether, getting the levels right.

Amy and I spent tons and tons of time listening to mixes, writing back with small suggestions. I was surprised we didn't drive her absolutely insane with this project. So much work, and she did a glorious job.

This is always a team effort. Our name gets put on the album, and we get the recognition as the band, but the amount of work and effort that goes into it from so many other people. Their work is just as... the load is equal to our work.

Wedge Monitors Versus In-Ears

Cris Cohen: I saw you guys perform here in Raleigh just a few weeks ago. I noticed that you guys seem to prefer wedge monitors, the speakers that sit on the ground, ss opposed to in-ears. Did you do that for the performance with the symphony as well?

Emily Saliers: Amy uses in-ears. So, she used in-ears with the symphony. She used in-ears in Raleigh. She always uses in-ears, unless we do a festival thing where it's... they call it a throw-and-go.

I tried in-ears many, many years ago. I didn't like them because I felt separated from the experience. But I'm about to go to in-ears I think, because they help save your voice. You can hear your pitch much better. You're not subject to the same changes in the sounds of the different rooms that you play.

But for the symphony, she used her in-ears and I used a wedge, because that's what I'm used to.

Cris Cohen: Was it tricky getting that mix down right? If only because you've got this massive orchestra blasting away behind you?

Emily Saliers: For me, I don't even put the orchestra in my mix. I put my guitar and vocal, and then I have a side monitor on the floor. And I put Amy's vocal and instruments in the side. Then I just hear the symphony live behind me. So my wedges are really not that loud, and that's how I find my balance.

Amy's got her own way of dictating what she wants in her ears to our monitor engineer, who's also been with us for years and years. He's so good, he just knows us so well. So, Amy will adjust string section, brass section, bring up the orchestra, bring up the harp, bring up the violins. Whatever it is that she wants, she can just tell Mike and he makes the adjustments for her ears.

I think she set the symphony up pretty loud. So, in that sense, she may get that swirling, massive, musical experience. And mine is a little more tame, because it's at a lower volume and it's coming from different places around. Rather than directly in my ears.

Cris Cohen: I was looking at the videos from the performance. Both of you have two microphones that you seem to be singing into. What was the purpose of that?

Emily Saliers: It's just another way to get a different sound in at the same time, that could sort of be melded in the mix. Each microphone had a different sound, a different purpose. There was blending in the final mix that had gone on, because of the two mics that were there.

A Changed View Of Their Songs

Cris Cohen: I'm curious, we've already talked about the massive amount of work that went into creating this experience. Did this whole process change how you viewed any particular song of yours?

Emily Saliers: That's a really good question. Gosh, I'll have to think about that for a second, stop and think about it. I just have to say that the arrangements, they bring the songs to life in a way that I didn't experience before then. And so now, even when Amy and I are playing as a duo, I hear those arrangements in my head.

You know how orchestral arrangements can be. They get used in movies all the time because they evoke emotion. They can make you feel things in a very big way, when the orchestra kicks in. I think it's the same way with these songs. To have that beautiful sound, now, as part of the landscape of the song, is profound. What I end up feeling is, those arrangements really bring the messages of the songs home.

I'll pick a song like “Mystery.” It's about a relationship, but it also describes the end of summer and what it feels like outside in the weather. It's describing these two people and the mystery of what's going on, both in the physical world and in their relationship.

The strings just make that like a movie inside my head. So, I think the arrangements just bring the songs to life in a new way. But I wouldn't say that they make me stop and think about the lyrics in a different way. They just sort of heighten the experience.

Songwriting

Cris Cohen: Along similar lines, have you found that this experience has affected how you write, going forward?

Emily Saliers: Well, that's a very interesting and good question. I'm in the midst of writing right now and so is Amy. We're going to make a new record at the beginning of 2019. I am thinking a lot about... The one thing I think about now is, quite honestly, I'm a little bit tired of just playing guitar through things. When I made my solo album that came out last August, Lyris Hung, who plays violin with us on the road… There was a lot of playing guitars straight through the songs. I know there's a place for that, but I think a lot now about placement of other instruments. I don't always want to hear an acoustic guitar, up in the mix, through a song.

So, I'm just thinking more broadly about the way a song can be produced musically. I'm sure that has something to do with playing with orchestras. Not having the strummy guitar, my guitar part, be such a large part of the musical picture.

It's not really changing the contents of the songs. There's a lot to think about politically and socially and otherwise right now, honestly.

Cris Cohen: Right.

Emily Saliers: But it is changing the way... or, not even changing, just broadening the way I might think about musical arrangements. I've started thinking a lot about Amy's vocal arrangements. That's something I really haven't done before. I can't help but think it's because I'm thinking a lot about where parts fit musically. So that's an interesting result of this whole symphonic journey, and also of making a solo record.

Cris Cohen: Yeah. I don't know. It almost sounds like now you have the kernel of the song, the foundation, and it sounds like you're looking at, "All right, there's multiple roads I can take this one down. Which one resonates the most?"

Emily Saliers: Yeah, exactly. Sometimes you don't know until you get in the studio and figure it out. I keep going back to my solo album. But for instance, I had to learn all the guitar parts, because I wasn't just playing through the songs in the studio. It was a very different approach. Lyris was very much like, "Well, we'll use this guitar part here and this other guitar part here." And she sort of paints with a brush like that.

Whereas Amy's and my way of recording all these years is, we play our guitars while we're singing. Having the guitars in the mix is an important part of the sound. I'm not talking about changing that drastically, I'm just talking about the freedom that comes with doing that. Rather than just playing a part all the way through the song.

Performing With Sugarland

Cris Cohen: Yeah. Kind of along those lines, I was looking through your guys' Facebook page. You posted this photo of you guys doing “Galileo” with Sugarland. What I thought was interesting was, one fan had commented that it seemed like you weren't sure what to do with your hands, since you didn't have a guitar in them at the time.

Emily Saliers: It probably looked like that. We're not used to putting our hands anywhere else but on a guitar. I have to say it was quite freeing. So now I didn't have to concentrate on guitar parts, and just to be able to sing. I loved it. Plus, Jennifer and Christian are so good. Jennifer's voice is just so big and glorious. It was a moment of joy. I can't remember what I did with my hands, but it probably did look a bit awkward because I wasn't holding a guitar.

But in terms of just singing and not focusing on guitar, really, really freeing. Really, really fun. Because it takes... it changes when you're playing at the same time. There are a lot of bands with lead singers who aren't playing instruments throughout the whole show. They're just focusing on their singing and their performance.

Oh my God, I just saw Janelle Monae in concert. Oh my gosh, she just blew me away on so many levels. You're not going to see me and Amy put down our guitars and start to dance, but there is a certain power to a show. She did play guitar some, but mostly she sang and danced. Her message is incredibly powerful. The show, the visuals were powerful. The band was amazing. The lights, the whole thing.

Yeah, I get a little bit of a... I don't know. An advanced middle-aged yearning for a different way of doing things sometimes.

Cris Cohen: That is an interesting point, just the whole idea that you sing differently when you're not... when your brain isn't split between focusing on vocals and focusing on the guitar part at the same time. I don't know. I wonder, would you write differently if you just though, "Okay, I'm just going to write vocals right now."? Or "Just record vocals and then figure out the guitar part later.”?

Emily Saliers: It's very hard for me to imagine writing like that. I really like using the guitar, obviously, it's what I do. I can't see it being as gratifying, not being able to play guitar, or maybe a little bit of keyboard, or whatever stringed instrument. I love the Ukulele to write with.

I mean, I could do it as an experiment and for fun. But I enjoy the integration of the instrument. That seems to be how the song, for me, best finds its way out into the open. It's also interesting to me that, some songs we record with the electric guitars on albums, but we can still play them acoustically. Like “Go,” for instance, has electric guitar all over. There's electric guitar even with the symphony record. It easily translates to an acoustic version.

Through my solo album, this was the struggle for me. I didn't write with guitar parts all the way through. When we went to do those shows with me and Lyris, and she’d play her violin, I have never gotten quite as comfortable with playing the songs, because I didn't play them all the way through on the record. Except for a song called “Train Inside,” that I play almost every night during Indigo shows now. Because I know the guitar part, I can play it all the way through, I'm used to it.

Lyris is like, "It doesn't matter, it's just a different incarnation." These songs hold on their own with just the acoustic guitar and the lyrics. But, I never have been able to make the full connection. So I'm pretty sure my most authentic and best way of working involves sitting with an instrument while I write.

Alternative Guitar Tunings

Cris Cohen: Speaking of “Train Inside,” you recently posted a guitar lesson video, where you show how to play that particular tune. The first thing you mention is how it's not in standard tuning of the guitar for that song. A couple months ago, when I interviewed Jonatha Brooke, she talked about her love for unusual tunings. Which I'm just finding fascinating. A) that the two of you are friends. And then B) that you both have this affinity for that.

Why do alternative tunings appeal to you?

Emily Saliers: Well, first of all for me, they take me to a different song. For instance, if I'm writing a song in the key of D, when I can't play that bottom string, it feels limiting to me at times. Unless I just want to play a very much simpler approach to the song. Sometimes that's what the song wants. But for me, if I drop that D string, it just gives me a lot more band width for the writing of the song.

And also, I grew up listening to Joni Mitchell, who is the queen of alternate tunings. I had her song books. I'd look at those and tune my guitar to those tunings. To be able to play the songs as I heard them on her albums, I can't describe the thrill that was. If you get close, it's not the same thing. So part of it was my love for Joni. The first time I heard The Story, and I heard Jonatha, and I heard those guitar chords, I was drawn to it.

If you do a whole open tuning, if there's an open key of E, or open D, there's a sort of drone quality to it that I find very propelling for certain kinds to songs to be written. That I find quite moving at times. It can take me to a song that wouldn't have been born if I'd played it in standard tuning.

Then there are some songs that just call for standard tuning. I just know that when I'm writing them, it's hard to explain. But I know that alternative tunings, or alternate tunings, I guess is what they call them, have opened up a whole new world in songwriting. Mary Chapin Carpenter taught me this tuning where you drop the lowest string to D and you drop the highest string to C. I wrote “Galileo” with that, “Cold Beer and Remote Control.” Like five or six. “Fair Thee Well.” A song called “Run.” Maybe close to 10 songs in that tuning.

Cris Cohen: Wow. So that just opened up a whole new world for you in a way.

Emily Saliers: It really did. I don't think there's an album that Amy and I have made where my songs didn't include some with alternate tunings.

Songwriting Workshops

Cris Cohen: Then also, one thing I talked about with Jonatha is, the songwriter's workshop that she does, that you have been a guest at. You're working with these up and coming, young songwriters. I'm curious, what do you take away from that experience?

Emily Saliers: You ask such good questions. It's so nice.

Cris Cohen: Well, thank you.

Emily Saliers: You know what? I just did a ... My friend Bucky Motter, who I've known in the Atlanta music scene for, oh my gosh, 30 years. She has a master guitar class, she teaches guitar. I went to that class, and she has little kids as young as 8 years old. And then, people who are probably in their 60s, maybe 70s, so it runs the gamut. And also in terms of the level of their ability to play the guitar.

I came away so inspired, purely by the growth of learning and playing. The joy of learning an instrument. People working on crafts. And when I do this songwriting... I'm getting ready to leave for Nashville on Saturday to start my own workshop. I always take away, for instance, I'm more about the narrative. I use a lot of imagery to get lost in my songwriting.

But there are a lot of students in the class who don't write like that. They either write very simply, non-poetically. Or, they write zany kind of lyrics that are just so clever, stuff that I could never do. So, it doesn't matter the level of your ability to play guitar or write a song. There's always something that I glean if I can't do that sort of thing myself. It just sort of broadens me and stretches me.

I'm also inspired by people who try to get better, to grow, to use their brains and their hands to make beautiful things, to make beautiful music. I learn a lot about that from those workshops. I learn about how important it is, if you want to grow, to spend time working on it. To me, songwriting is like a business, after I ... Not a business, but like a schedule business. After I do this interview, I'm going to go down and from this time to this time I'm going to work on my new songs. I have no idea what's going to come, what instrument I'm going to use, what tuning, what key.

Then I'll go down there and maybe I'll start in C, start an idea, get maybe 20 minutes in, lose interest. Throw a capo on, see what's better up the fret. Maybe that leads me to another song, try a different tuning. Who knows what will happen? But between the hours of blah blah and blah blah, I'm at my office.

When I do those songwriting workshops, there are exercises and times that the students spend working on their songs, and it's inspiring. They take a lot of concentration. They're four days long, the workshops, and they're all day long, and sometimes into the night. You're doing a lot of listening with the students. You want to be encouraging while still... and you want to point things out while still realizing that it's subjective. You know? Which is kind of a fine balance to find.

So, they take a lot of energy, but it's just the most worthwhile experience, to be in the process of creating with other people.

Cris Cohen: When you go down to your own studio, and obviously you're very disciplined in saying, "Okay, I'm going to work at this and devote myself to this for so many hours,” how do you gauge productivity? For someone like myself, it seems like I could go in and if I don't come out with something like a song, I would feel despondent. Is it the attempt, is that as valuable as the result?

Emily Saliers: Well, I don't know if it feels as valuable, but it is as valuable. Because the only way to ever get to a song that's completed is to just start bouncing around ideas. It's hard to write a song. It's not easy. It's kind of mentally draining. Sometimes I'll start to sit down and write a song and tears will start coming to my eyes. It's like, "Okay, just open up." I just open up and dig around and see what's in there. I look at my notes, listen to my voice memos of ideas that I've recorded.

So it's like practicing. As a kid I never wanted to practice. I took classical guitar for two years. I didn't want to practice, but I did practice, and I got better because I practiced. There's no way I'm going to write a song unless I go down there and grind it out, try different things.

I just finished a song that's for Amy's and my new album that we'll make. I finished it, I thought I was done. I was like, "Okay, that's done." But it was nagging at me a little bit. I thought, "Maybe I should go back and take a look at these lyrics. Maybe the bridge is too long." I just had these nagging thoughts. And so I went back and I really completely re-vamped it. The idea and the nugget of the song remained the same, but the bridge is half as long as it was. I changed a lot of the lyrics and images and now it's done. I know it's done.

So, I think the process, while it may not feel as satisfying, like when you really get to that point where you know you have a song, it is a really, really good feeling, but then it's like, "Oh man, if we're going to make an album, I have to write five more."

We work hard at our music. The best job in the world, but it still involves discipline and work, and hammering away at things that never come to fruition sometimes.

Tig Notaro

Cris Cohen: Finally, just as kind of fun question, regarding a recent Netflix special you appeared in, how would you rate Tig Notaro as a drummer?

Emily Saliers: I thought she kept a steady beat. For someone who's not used to playing drums, and she's recording a live television special. There's all the technical things you have to think about too. I thought it was awesome. It makes me smile to think about it. Because you know, Tig is so dry, but she just got behind the drums and just played the hell out of them, you know.

Cris Cohen: Yeah, I was impressed. I didn't see that coming.

Emily Saliers: I didn't see it coming either, and I was impressed too. It just made us laugh and feel good. Any time the drums kick into a song, things get better, for me. I love it when drums kick into a song and I'm happy, I'm ready to go.

Cris Cohen: Then finally, because you've been doing interviews regarding this album. Is there anything that you want to discuss about the new album that you really haven't had a chance to talk about or that people haven't asked you about?

Emily Saliers: I think we've gotten a lot of responses from people listening to the album. They tend to really love it. It's gratifying. Some people just listen to music and that's it, that's great, that's what you want. If you have a good turn table and speakers, and you put that on and you blast it. Everything that we had, with the team that we had, was put into making that album sound as good as possible. It was many, many, many, many, many countless hours of work to achieve that.

So, I think if you put it on and you play it and you love it, that's the whole point. But I would also just remind people who are interested in it that, there was a recording engineer who did the best of his abilities. There was a monitor engineer. There was each individual player. There was the conductor. There was me and Amy. There was our guitar tech, who is making things run smoothly. There were all the microphones and the placements.

And then, there was the engineer. Then there was the mastering and cutting the lacquers. And so, I sometimes think about what goes into the making of an album, it's tremendous to think about. But this album in particular, it's the biggest team that's ever been assembled that we've worked with. I think it's a cool thing to stop and think about.

In the end, the point is that people put it on and love it.

Bands To Fans: We help musicians tell their stories via social media, websites, etc.